| SEARCH |

-

Nov 17, 2015

Reflections on a three-decade legacy

The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) will come to a close at t...

-

Nov 17, 2015

Use of and access to content on this website

Text and images produced by IGBP in house are free to use with appropriate credi...

-

Nov 12, 2015

Bella Gaia performance and panel discussion to mark IGBP's closure

A musical performance by Bella Gaia will celebrate the achievements and legacy o...

-

Towards Future Earth:

evolution or revolution?

During its three decades of existence, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Pro...

-

A personal note on IGBP and the social sciences

Humans are an integral component of the Earth system as conceptualised by IGBP. João Morais recalls key milestones in IGBP’s engagement with the social sciences and offers some words of advice for Future Earth.

-

IGBP and Earth observation:

a co-evolution

The iconic images of Earth beamed back by the earliest spacecraft helped to galvanise interest in our planet’s environment. The subsequent evolution and development of satellites for Earth observation has been intricately linked with that of IGBP and other global-change research programmes, write Jack Kaye and Cat Downy .

-

Deltas at risk

Around 500 million people worldwide live on deltas, but many of the world's deltas are sinking due ...

-

Climate change: the state of the science

A new data visualization released on the first day of the plenary negotiations at the UNFCCC’s clima...

-

Climate Change:

the State of the Science

Videos now online from the Stockholm public forum to mark the launch of the IPCC's climate report, 2...

Anthropocene

The idea that humanity has driven the planet into a new geological epoch has been around for a century or more. But recently, it has begun to gain momentum.

Earth is about 4.5 billion years old. Geologists break this history down into blocks of time known as eras, epochs, periods, ages. Eras and epochs are usually separated by a major change.

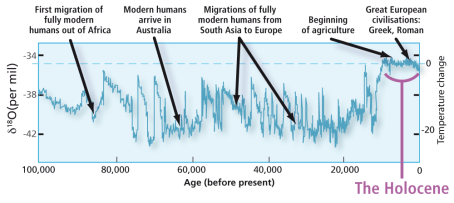

The epoch we are in is the Holocene. It began as the last Ice Age began to shrink, around 12,000 years ago.

Modern humans first stepped out onto African plains 200,000 years ago. But it has only been during the Holocene that human civilization has developed.

Throughout our history, humans have had significant local effects on the environment. That has now changed. Since the industrial revolution in 1750 have humans have grown into a global force to be reckoned with.

A new epoch?

The notion that we have entered a new epoch and that it should be known as the Anthropocene was first suggested in 2000 in an article appearing in the IGBP Global Change Newsletter. The authors of the article, IGBP Vice Chair at the time, Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen, and Eugene Stoermer argued that Earth had recently crossed a threshold into a new epoch.

Crutzen followed this original article with a commentary in the journal Nature in 2002, the Geology of Mankind.

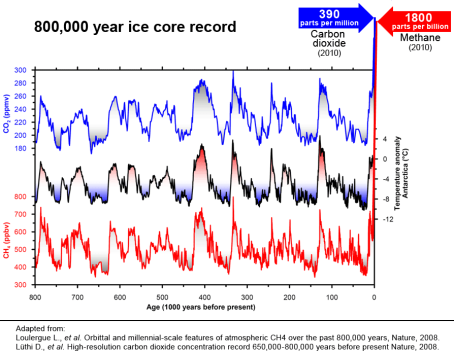

In this article Crutzen says, “The Anthropocene could be said to have started in the late Eighteenth century when analysis of air trapped in polar ice showed the beginning of growing global concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane.

Arguments for a new epoch, the Anthropocene, include:

- In the last 150 years humankind has exhausted 40% of the known oil reserves that took several hundred million years to generate

- Nearly 50% of the land surface has been transformed by direct human action, with significant consequences for biodiversity, nutrient cycling, soil structure, soil biology, and climate

- More nitrogen is now fixed synthetically for fertilisers and through fossil fuel combustion than is fixed naturally in all terrestrial ecosystems

- More than half of all accessible freshwater is appropriated for human purposes, and underground water resources are being depleted rapidly in many areas

In the video below, former IGBP Executive Director Will Steffen discusses the Anthropocene.

The Earth system is in a "no analogue state"

The planet is now dominated by human activities. Human changes to the Earth system are multiple, complex and interacting. They are often exponential in rate and globally significant in magnitude. They affect every Earth system component – land, coastal zone, atmosphere, cryosphere and oceans.

The human driving forces for these changes are equally complex, interactive and frequently teleconnected across the globe. The magnitude, spatial scale, and pace of human-induced change are unprecedented in human history and perhaps in the history of the Earth. The Earth system is now operating in a “no-analogue state”.

Until the industrial revolution humans and their activities played an insignificant force in the dynamics of the Earth system. Today, humankind has begun to match and even exceed nature in terms of changing the biosphere and affecting other facets of Earth system functioning.

The magnitude and pace of human-induced change are unprecedented. The speed of these changes is on the order of decades to centuries, not the centuries to millennia pace of comparable change in the natural dynamics of the Earth system.

Drivers of change

Over the past two centuries, both the human population and the economic wealth of the world have grown rapidly. These two factors have led to a massive hike in consumption. We can see this in agriculture and food production, forestry, industrial development, transport and international commerce, energy production, urbanisation and even recreational activities.

Almost seven billion people now live on Earth. All share basic human needs: water, food, shelter, good health and employment. The ways in which these needs are met are critical determinants of the environmental consequences at all scales.

In the developed world, affluence, and more importantly the demand for a broad range of goods and services such as entertainment, mobility, and communication, is placing significant demands on global resources.

Between 1970 and 1997, the global consumption of energy increased by 84%, and consumption of materials also increased dramatically.

While the global population more than doubled in the second half of the last century, grain production tripled, energy consumption quadrupled, and economic activity quintupled.

Although much of this accelerating economic activity and energy consumption occurred in developed countries, the developing world is beginning to play a larger role in the global economy and hence is having increasing impacts on resources and environment.

Almost all activities in all countries demand energy. Fossil fuels provide the bulk of this energy, which leads to emissions of carbon dioxide, other trace gases and small particles (aerosols).

Industrialisation has led to considerable air and water pollution associated with the extraction, production, consumption and disposal of goods.

Over the past three centuries, the amount of land used for agriculture has increased five-fold.

Furthermore, large areas of land area have been lost to degradation, due, for example, to soil erosion, chemical contamination and salinisation.

IGBP closed at the end of 2015. This website is no longer updated.

-

Global Change Magazine No. 84

This final issue of the magazine takes stock of IGBP’s scientific and institutional accomplishments as well as its contributions to policy and capacity building. It features interviews of several past...

-

Global Change Magazine No. 83

This issue features a special section on carbon. You can read about peak greenhouse-gas emissions in China, the mitigation of black carbon emissions and the effect of the 2010-2011 La Niña event on gl...

-

INTERGOVERNMENTAL PANEL ON CLIMATE CHANGE:

How green is my future?

UN panel foresees big growth in renewable energy, but policies will dictate just how big.

-

UK:

'The Anthropocene: a new epoch of geological time?'

Royal Society, Philosphical Transactions A