| SEARCH |

-

Nov 17, 2015

Reflections on a three-decade legacy

The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) will come to a close at t...

-

Nov 17, 2015

Use of and access to content on this website

Text and images produced by IGBP in house are free to use with appropriate credi...

-

Nov 12, 2015

Bella Gaia performance and panel discussion to mark IGBP's closure

A musical performance by Bella Gaia will celebrate the achievements and legacy o...

-

Towards Future Earth:

evolution or revolution?

During its three decades of existence, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Pro...

-

A personal note on IGBP and the social sciences

Humans are an integral component of the Earth system as conceptualised by IGBP. João Morais recalls key milestones in IGBP’s engagement with the social sciences and offers some words of advice for Future Earth.

-

IGBP and Earth observation:

a co-evolution

The iconic images of Earth beamed back by the earliest spacecraft helped to galvanise interest in our planet’s environment. The subsequent evolution and development of satellites for Earth observation has been intricately linked with that of IGBP and other global-change research programmes, write Jack Kaye and Cat Downy .

-

Deltas at risk

Around 500 million people worldwide live on deltas, but many of the world's deltas are sinking due ...

-

Climate change: the state of the science

A new data visualization released on the first day of the plenary negotiations at the UNFCCC’s clima...

-

Climate Change:

the State of the Science

Videos now online from the Stockholm public forum to mark the launch of the IPCC's climate report, 2...

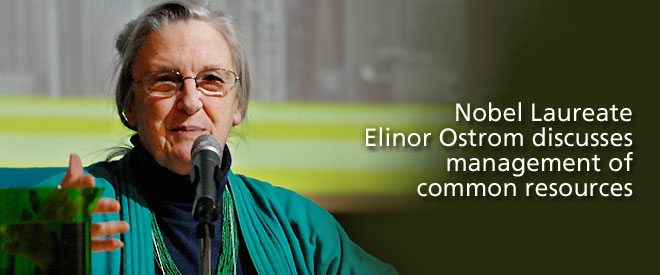

Reflections on

Governance

What is the best solution to tackling climate change? There is no panacea, and we have to experiment with multiple approaches, Elinor Ostrom tells Ninad Bondre.

Winning the Nobel Prize in economics must have really put the spotlight on you.

Yes, the past few months have been very busy. I am still getting requests for travel in 2010, at a rate of three or four a day. But my travel itinerary for the year is already fully booked.

Your work over the past decades has highlighted many examples where local communities organised themselves to manage natural resources sustainably. Do local communities do a better job of managing resources than national governments?

That depends very much on the specific context. Decentralisation has become somewhat of a mantra in the recent past, and there is a tendency to consider this as a panacea. But this is just as naïve as saying that the solution to resource-management problems is centralisation. Local management has its benefits but it cannot be used as a quick and dirty blueprint to solve all problems.

There are parts of the world where people had centuries of experience in managing the natural resources that they depended on. In many instances,

the resources were taken away from them. If we are to now return the control over the resources to the communities, several questions need to be answered. For example, how long has it been since the resource in question was taken away from the community? Does the community still have people with the indigenous knowledge that would be essential to manage the resources? I have gone to meetings where forest officials have simply said: “Now it’s yours”. But they forget that what is being handed over is often a resource that has been degraded by years or decades of poor management. It does not make sense to abruptly transfer it to local communities and expect miracles.

Following up on that, you have cautioned against the tendency to believe in panaceas for problems of sustainable management of social-ecological systems.

Yes, this is addressed in a 2007 special feature in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, entitled “Going beyond panaceas”. Studies in this issue highlight the pitfalls in governance approaches informed by notions of a universal remedy. At one end of the spectrum, the belief that government ownership is the best way to manage natural resources – forests, for example

– has in some cases led to a marked reduction in the resource.

At the other end, imposing decentralisation as a remedy without a proper understanding of the local society has triggered ethnic conflict. Social-ecological systems are complex and nested, and resource users around

the world vary widely in their preferences and perceptions. Such systems are not amenable to being characterised by simple models.

Global commons – resources that are shared by the world – pose special challenges, which you have alluded to in your 1999 Science article. What have we learned about the management of such resources in the past decade?

We have found that the oceans and the atmosphere are fundamentally different when it comes to applying local strategies to solve global problems

For the oceans, we do not yet have many local-scale experiments, the results of which would apply globally. Community management works well in the case of coastal fisheries, where people can know one another, sell their fish in one place and where there can be monitoring. This is difficult to achieve at the global scale. In the case of the atmosphere, steps taken at the individual and community levels can have global impacts. For example, an immense amount of energy goes into heating buildings, and local actions aimed at reducing such consumption can be very effective in reducing greenhouse-gas emissions globally. Actions at the local scale do not necessarily solve the global problems; global action is also needed. But we could be taking many more steps locally and regionally, and indeed, more and more are being taken.

The Copenhagen conference is being viewed in some quarters as a failure due to the inability to reach an international agreement. Do you think that the exclusive focus on a global agreement is inhibiting actions at other levels?

Absolutely. If we think that action is important only at a global scale, we are sitting around twiddling our thumbs when we could do much more. I would encourage efforts at all scales: local, regional and global. The problem of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions has been framed exclusively as a global issue; as a result, it is sometimes difficult for policymakers and citizens to appreciate that there are many important actions that can be taken at the local scale. This was one of the difficulties that the Cities for Climate Protection campaign faced. Yet, there are several examples of successful efforts to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions that are being taken at local and regional scales, which I discuss in a policy paper that I wrote for the World Bank last year, entitled “A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change”.

It is a fact that international efforts during the past several decades have failed to come up with a fair and enforceable agreement on reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. It is not advisable to wait for the perfect global agreement while ignoring important actions regarding adaptation and mitigation that could be taken at other levels. But not only this, there is empirical evidence to suggest that problems have been addressed successfully as well as unsuccessfully at all scales – local, national and international. The polycentric approach advocates complex, multi-level systems to tackle what is a complex, multi-level problem. Given the nature of the problem, building the system required to execute this approach will of course take time, but recognising

the need for such an approach is important enough.

Governance is the subject of ongoing research. But would it be correct to say that trying and testing various systems should continue in parallel?

Yes. We do need as good a foundation as possible to base action on. But there are some scientific questions that will take us a while to answer. Meanwhile, we should be experimenting with diverse institutional changes, and monitoring them carefully so that we can learn from such experiments.

Simple mathematical models can work very well for some questions but often do not work that well with complex systems and in evaluating policy

choices. Concrete actions and experimentation can help us to understand why the changes work in particular contexts and not in others.

You have spoken about the need for embracing the concept of social-ecological systems. Do you think international programmes such as IGBP are doing enough?

I think that they could do more. A major challenge for such programmes is to develop a common language that crosses disciplines. Disciplinary boundaries tend to be etched in stone, and there is a big divide between the social sciences and the ecological sciences, which have developed independently. We need to get a real conversation going between these two broader disciplines. Social-ecological systems represent a complex whole, but different disciplines approach such systems in diverse ways. Some of my recent work, and that of others, has focused on how we can develop a common language that will help us move forward, and I am currently developing this further with colleagues in Europe. In fact, they are beginning to use this framework to design new empirical research.

In the 1980s, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in Canada used its own model for stock regeneration of northern cod, overriding the concerns

about collapse raised by local fishers. The stock collapsed soon after, in 1992, compelling the government to suspend cod fishing in Canadian waters. This came at a considerable cost to local fishing villages that had managed fish stocks effectively until then.

For more details and references see Ostrom E (2009) "A polycentric approach for coping with climate change". Policy research working paper WPS5095.

The World Bank.

Forests are a source of livelihood for tens of millions of people around the world. And by drawing down atmospheric carbon dioxide, they also contribute to stabilising greenhouse-gas concentrations. But whether these two types of benefits go hand in hand or conflict with each other remains to be fully understood. To shed more light on this issue, researchers recently analysed data for 80 forests in 10 different countries. They focused on three aspects: forest size, autonomy at the local level to make rules regarding forest management, and ownership (whether by local communities or by national governments). They found that a combination of larger forests and greater local autonomy lead to above-average benefits in terms of livelihood as well as carbon storage. Government ownership was found to result in high livelihood benefits, but this came at a cost to carbon storage. The researchers suggest that international initiatives aimed at reducing emissions by encouraging forest preservation should explore the option of transferring the ownership and management of larger tracts of forests to local communities.

Chhatre A and Agarwal A (2009) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 17667-17670.

In 2006, the State of California passed a law aimed at reducing greenhouse-gas emissions in the state and bringing them down to 1990 levels by 2020 (a reduction of approximately 25 percent; see http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/facts/facts.htm for details). This entails substantial cuts by major industries. The state seeks to achieve this by a market-based, cap-and-trade programme.

Local governments in Denmark operate plants that incinerate household waste to generate power and heat. The Horsholm plant, for example, is owned by five different local communities. As The New York Times reports, “Sixty-one percent of the town’s waste is recycled and 34 percent is incinerated at waste-to-energy plants.” The advantages that the plants provide in terms of waste disposal and cheap heating ensure that most communities in Denmark are eager to have such plants in their neighbourhoods.

For more information see http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/13/science/earth/13trash.ml?pagewanted=1&ref=earth.

IGBP closed at the end of 2015. This website is no longer updated.

-

Global Change Magazine No. 84

This final issue of the magazine takes stock of IGBP’s scientific and institutional accomplishments as well as its contributions to policy and capacity building. It features interviews of several past...

-

Global Change Magazine No. 83

This issue features a special section on carbon. You can read about peak greenhouse-gas emissions in China, the mitigation of black carbon emissions and the effect of the 2010-2011 La Niña event on gl...

-

INTERGOVERNMENTAL PANEL ON CLIMATE CHANGE:

How green is my future?

UN panel foresees big growth in renewable energy, but policies will dictate just how big.

-

UK:

'The Anthropocene: a new epoch of geological time?'

Royal Society, Philosphical Transactions A